..what if we slowed things down?

We tend to take it for granted that life in our modern world is hectic and that people are stressed. We grumble about the economy, we hear that it must keep growing, and we dread the word recession. Many of us have not questioned why this all is as it is, or whether there are other systems that might be more beneficial for us. Some people have been asking questions and are creating different systems: exploring new ways of living.

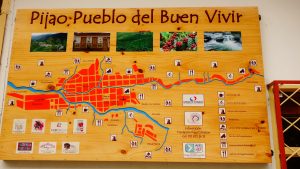

This piece was inspired by time in a little town called Pijao, an hour outside of Armenia, Colombia where they have decided, as a community, to change the way they do things. Pijao is South America’s first Slow City. I had heard about Slow Food and the Slow Movement in Europe and slowing down made perfect sense to me, but I had not talked to people living with this idea and putting it into action. So I visited Pijao (twice in the end) to find out what it actually means to go more slowly and what difference it makes in day-to-day life.

In order to talk to you about slowing down and what it means for a town, I would like first to frame this change of gear within our current economic system by describing why some things are the way they are.

“Economics is described as the social science that analyses the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services within our society (towns, cities, countries). The term originally came from the ancient Greek word oikonomia, (oikos = house) and nomos = custom or law. This translates to mean “rules or management of a household.” The person who managed the house was traditionally the housewife and the person who generally managed the land associated with the household was the farmer. So the first economists were families taking care of their home and livelihood.

Our economic system is based in money as a medium of exchange. Before money we traded using a bartering system: exchanging goods and services for other goods and services. Our current monetary system was developed in the US in the 1800’s and it was based on what was called The Gold standard, which meant that paper currency had guaranteed value tied to something real i.e. gold . This is known as commodity money. It had its problems such as: when miners found new gold deposits, gold prices and currency values dropped. The gold standard came to an end in 1933 when President Roosevelt made the private ownership of gold (except for the purposes of jewellery) illegal. The Bretton Woods System, enacted in 1946 created a system of fixed exchange rates that allowed governments to sell their gold to the United States treasury at a fixed price. In 1971 the US economy was under pressure due to the expense of the Vietnam war and when France decided to exchange all its dollar reserves for gold President Nixon decided, under what was called the Smithsonian agreement (or the Nixon Shock!), to end the ability to convert dollars to gold. This was a major move in modern day economics because then, for the first time in history, we severed links between major world currencies and real commodities i.e. money was separated from nature. This has had major consequences on the global economy and how we relate to our environment.

This move led to a monetary system that we now use in almost every country, called fiat money. Fiat literally means a decree or an order and what it means in practical terms is that governments can issue their own money. Fiat money is created and is used only as a medium of exchange, it has no intrinsic value of its own, only the value that governments’ uphold, and the value that is set by its supply and demand and the supply and demand for other goods and services in the economy.

But governments actually only make 3% or our money (this is the notes and coins that we use) the other 97% is created by banks. This process of creating money is called Fractional reserve Banking. A bank is legally required to hold only a percentage of its reserve i.e. only a percentage of the physical money reserves, on site. The balance is loaned out. If a bank is required to hold a 10% reserve then they can loan out 90%. But they don’t actually hand out the 90% in cash. They keep the original 90% and create another 90% and loan that out..(yes…just like magic!). This is how they essentially create money out of thin air: this is called credit creation and is known as a debt based monetary system: it is reliant on loans and people being in debt to create money i.e. all of your money is money that is owed to banks by someone else.

Here is an example from a website: A person X with €100 goes to the bank and deposits it. Now the bank can loan €90 out of this €100 and keep a reserve of €10. Then let’s say person Y takes a loan for €90 for paying something to Z. Z receives the €90 and has to keep it somewhere and he goes into some bank and deposits this €90. Now the overall money supply of the entire system is $100 (deposits in first bank) + €90 (deposits in second bank) =€190. Then this second bank can loan €81 (keeping €9 as a reserve) and this process continues until you cannot divide up the currency anymore.

As money is not based on a fixed ‘thing’ (like gold, silver etc) the amount of money in our system can, and does, keep growing (the effect of this growth is called inflation: the devaluation of money). And it keeps growing through lending and then on top of that through interest on loans. In theory this system can keep growing indefinitely. But our physical planet is not a theory.. it has a finite carrying capacity.

“Given that the financial system requires ever higher levels of indebtedness from the general populace for its solvency, it is vital that the indebted “victims” who must sink deeper into debt for the system to survive do so voluntarily and willingly and are not made aware of the consequences of purchasing consumables with debt money.”

It is no wonder that we feel stressed and under pressure.

“Modern slaves are not in chains, they are in debt”

And one more thing that I want to mention is how our economic progress is measured. I am sure you have heard of GDP (Gross Domestic product). This concept was created by Adam Smith, said to be the father of Capitalism, in the 18th Century. GDP attempts to denote the state of the economy in one number i.e. the total market value of all final goods and services produced in a country in a given year. It is equal to total consumer investment and government spending plus the value of exports, minus the value of imports. GDP can be developed in a number of ways, the main one being: the expenditure approach, which adds up the outputs of every type of enterprise to give a total.

|

Our economy is reliant on the use of natural resources to create ‘goods and services’, but GDP does not take into account the depletion of natural resources that are required to produce them. The harvesting of forests, whether plantations or ancient tropical forests, adds to the market value of wood to the economic. And GDP does not distinguish between monetary transactions that genuinely add to well-being and those that take away from it: GDP includes monetary transactions from crime, legal fees, and other signs of social breakdown as economic gains. The more you spend the better it is for the economy; the more we drill and chop and dig the better it is for the economy. And GDP is frequently used as a proxy measure of ‘quality of life’. We assume that a higher GDP will mean a higher quality of life, but by counting only money transactions GDP omits much of what human’s value and what serves basic needs e.g.

- Unpaid services: care for children and the elderly, cooking, washing, community and volunteer work.

- The value of time spent in recreation, relaxation and social activities.

- The crucial contribution made by the natural environment to the economy: pure air and water, productive topsoil, moderate climate, the protection from the sun’s harmful rays.

The underlying contradiction of our current global economic model, is between people’s desire to live well within the system versus our collective need to live within the means of our planet; the model is reliant on increasing supplies of materials, goods, products and components, but doesn’t take into account that ultimately the source of these supplies is finite. So if we continue on this trend of continuous growth we will literally devour the planet….

I find all of this pretty depressing to be honest, and its probably why few people are talking about it. But we really REALLY need to be talking about it. It is good to know that there are people looking at economics in different ways and it is interesting that within economics there exists a subfield of study and it is called Environmental economics: “Environmental economists study the economics of natural resources” (whereas standard economists don’t consider it…..)

“Economics needs to be considered in relation to the society within which it exists and within the environment upon which it is reliant. Environment, society and economy are often listed as ‘the triple bottom line’ as a means to describe sustainable development but they are not three equal concepts. Functionally the economy is part of society and this in turn is a part of the biosphere so instead of being described as three interlocking circles they need to be described as three concentric circles.” (Chambers, Simmons and Wackernagel)”

There are many alternatives and options and I just want to mention one: an example of an alternative to GDP is called GPI: the Genuine Progress Indicator. In its calculation GPI excludes: the cost of crime, pollution and costs to the natural environment, health care expenditure of preventable diseases, loss in infrastructure from natural disasters and war, foreign debt (in GDP this is seen as positive government spending).

GPI is being used by some organisations, but unlike GDP, which only deals in monetary sums, GPI deals with qualitative sums also e.g. putting a price on the cost to the natural environment. These figures are subjective: it depends on the value you place on aspects of nature: what value do you place on the bees, on the amazon rainforest, on the Atlantic ocean, on a small stream in the Wicklow mountains? This is called putting a value on natural capital. People and what they offer in society can be referred to as social capital. There are actually many studies and guides that put monetary values on natural capital, so figures are available, but because GDP is used so prevalently, there is huge inertia to changing to another system. But we do need to change this current system: our planet is not a commodity to be bought and sold, it is the home for all of our communities and it is our job to take care of it, not sell it out from underneath one another.

Coming together in community, in eco-communities and community projects is a way to strengthen our social connections and our connections to natural resources: especially in projects that include working with food production: fruit and vegetable crops etc and the provision of local services. This is actually what the Slow Movement is doing, it is what it is about: placing value on the community, our environment, on connection and our collective creativity.

View over Pijao

View over Pijao

Citta slow , which means Slow City, was started in Italy and was inspired by the slow food movement. Slow Food is a global, grassroots organisation, founded in 1989 to prevent the disappearance of local food cultures and traditions, to counteract the rise of fast life and combat people’s dwindling interest in the food they eat, where it comes from and how our food choices affect the world around us.”

In 1999 Paolo Saturnini the former past Mayor of Greve in Chianti, Tuscany was inspired by the Slow Food movement to consider the quality of life of an entire town and so he founded Cittaslow. The main goal of Cittaslow is to enlarge the philosophy of Slow Food into local communities and to the governments of towns by honouring the authenticity of local production methods, being respectful of people’s health, Honouring Local creativity and local enterprise in all its forms: honouring local craft and traditions, art, theatre, shops, cafés, restaurants, respecting traditions through the joy of a slow and quiet living.

In order to become a member, towns and cities need to comply with the Citta Slow guidelines: there are 72 in total and they are divided into a number of categories:

- Energy and environmental policies

Parks and green areas, renewable energy, transport, recycling, etc. - Infrastructure policies

Alternative transport, cycle paths, street furniture, etc. - Quality of urban life policies

Requalification and reuse of marginal areas, cable networks (fibre optics, wireless), etc. - Agricultural, tourism and artisan policies

Prohibiting the use of GMO in agriculture, increasing the value of working techniques and traditional crafts, etc. - Policies for hospitality, awareness and training

Good welcome, increasing awareness of operators and traders (transparency of offers and practised prices, clear visibility of tariffs), etc. - Social cohesion

Integration of disable people, poverty, minorities discriminated, etc. - Partnerships

Collaboration with other organizations promoting natural and traditional food, etc.

Mónica Flórez was born in Pijao but moved away for many years. The little town did not have a lot going for it: after the failure of The Coffee Pact in 1989, a major earthquake in 1999 and a guerrilla invasion in 2001 that set up roadblocks , Pijao had become isolated and was generally viewed as hostile and dangerous. Through their isolation the local people lost hope and confidence. Monica witnessed this apathy and hopelessness in the town, and when she heard about Cittaslow she recognised that she could do something to bring about positive empowering creative change. She moved back tot he town and initated a series of meetings. There was resistance initially but Mónica continued to champion the tenets of Cittaslow and the Pijao Cittaslow Foundation was born in 2005.

“We began working with the culture, public awareness, architectural heritage; the people just didn’t recognise it all. We involved the children, we improved education, we started to recuperate our building facades and to understand our own environmental richness. …Little by little many started to understand that doing things slowly and with good conscience was going to bring benefits for everyone.”

So, in November 2017 I took the two-hour bus journey from Armenia and I remember wondering as I left the city about what Pijao might be like. I was really unimpressed with the countryside outside of the city and was beginning to regret having listened to my friend who had mentioned this project to me in the first place. But I trusted my friend, he had given me some amazing tips on very real and authentic places to visit in Colombia. As I looked out the window the landscape began to change as we climbed up into the forest and coffee covered mountains on winding roads with a growing view of the plains around Armenia. I could feel I was heading somewhere special.

We arrived in the quiet central park in Pijao and the friendly bus driver and passengers were eager to help me with directions. I went for a coffee by the park to get my bearings and found myself chatting with some locals, they directed me to a nearby hostel. There isn’t much accommodation in Pijao it seems but the proprietor of my hostel knew all about Cittaslow and was helpful in giving me suggestions of places to see and people to chat to. On walking around everyone I talked to knew about the project, its not surprising, as Pijao is a small town of 5,700 living in the urban centre.

One of the first people I met was Gerardo, a retired teacher and one of the original locals to engage in Cittaslow. Gerardo is a wonderful friendly kind and huge hearted man and I could not have asked for a more thoughful person to show me around. We walked around the town together: he talked about various aspects of Cittaslow and introduced me to people as we went. He told me about how they all first met and how they began to talk about how they could make simple changes in the community. The initial projects focused on the restoration of facades: Quindío is famous for its colourful building facades and in Pijao their buildings needed some TLC. These first steps were a way for everyone to get involved and improve the overall look and feel of the town, and it proved to be a positive way to motivate people and let them see that simple changes could make a big impact. The community began to get a glimpse of what they could achieve together.

The streets of Pijao

We met the women who sort the local recycling – by hand. There is no municipal recycling scheme and waste is not yet separated at home, it is brought to a nearby large sorting shed and a group of women separate it. It is not the most effective way of dealing with recycling but by this method they can sell some materials for reuse and have others recycled and therefore reduce their municipal waste. They are working towards developing this system. This is how it goes with Cittaslow: start simply, observe, learn and evolve.

The lovely ladies sorting the local waste

I got to see the local HEP (hydro-electrical power) station where the energy of the river is converted into electrical energy for use in the municipality. And we talked about water in general in Pijao: one of the main reasons that Pijao is not yet fully certified as a Cittaslow town is because they, as yet, do not have a water filtration system for potable water. This is not uncommon in Colombia: larger cities like Bogatá and Medellin have potable water but many areas, like Pijao do not have the funds to pay for it.

HEP station

Gerardo brought me to meet Doña Mary a woman who rears heritage chickens: these are the older breeds that are hardier live longer and are part of the heritage of the local area. It was a delight to meet this forthright and passionate grounded woman and talk about these rare and beautiful breeds that produce a variety of different coloured eggs. The hens are fed scraps from Doña Mary’s wonderful organic garden where she produces a huge variety of fruit, vegetables and herb in a small site. We happily sat and chatted in her garden, sipping herbal tea made from a mixture of fresh herbs from the garden and listening to the contented clucking of the happy hens. The community has started the Happy Hen projects which encourages the breeding of heritage breeds and provides locally produced organic eggs for the community.

Doña Mary’s happy hens

One of the main crops in this part of the country is Coffee and I had the chance to visit three coffee farms in the area. Gerardo brought me to Finca Granada where I met Jesús Maria Pedraza’s a retired lecturer in coffee production who in the last 8 years has developed his own coffee farm following the philosophy of Cittaslow. I spent a wonderful morning chatting at length with Jesús about the incredible variety of plants that he grows with the coffee to enhance the diversity of the natural systems of his farm. We got to see his stunning organic garden, his dogs, heritage breed hens, ducks and geese. I just loved this farm and was in heaven to see the love and care he took in managing his homestead and producing very fine coffee indeed. Which to my delight is produced for the Colombian market only: most coffee produced in Colombia is exported: the poorest quality coffee is usually kept for the national market.

Corn growing as one of 17 varieties of plants grown with coffee on Finca Granada

One day I walked into La Floresta cafe and I got to meet the proprietors Carlos and Orphelia. They grow and process their own coffee, they have created new ways to season and brew their coffee and have even created a delicious infusion from the fruit of the coffee. While I was chatting a tour group arrived and they very kindly invited me to stay for the coffee tasting and I got to sample a variety of the wonderful coffee that they produce. Later I went back and happily chatted some more and I learned about how they have changed their lives to dedicate themselves to growing high quality organic coffee, which just the day before I talked to them, had won the regional prize for best coffee.

Coffee at la floresta

In Café Luxman, the first cafe that I had visited by the central park, I met Victor the proprietor and coffee producer and he kindly brought me to see his coffee farm where he is planning to move and is putting Cittaslow ideas into action. It is located way up the mountains on an old family site with truly stunning views. He is developing an ecological coffee farm and has planted 200 trees on is 7hectares of land. He is cutting out non indigenous species and making charcoal and reintroducing local indigenous species.

View towards Pijao

Making charcoal

At the Citta Slow foundation shop la Tienda De buen Vivir I met Layva Sophia who, very passionately, talked to me about the products being sold in the shop: all local goods with mostly local coffee and chocolate. We talked about the different chocolate producers in particular: most are producing small batches for sale locally, and there are a number of foreigners producing chocolate in the area. This seemed to be worrying locals to an extent as locals coming in is pushing up land proces but there was also a sense of excitement mostly about what they could achieve together. I met local shop and business owners including Fernando Uran a passionate baker with a huge love for great bread and for bringing groups on cycling tours in the local area: which is packed with stunning walking and cycling routes.

I learned about how crops are being farmed and about some of the problems that the communities face in this area: I have talked about coffee which is a major crop in the area and another major crop is Avocado. I wasn’t aware of the many different varieties of Avocado that there are. The Hass variety is the small rough skinned green ones that we find in supermarkets in Ireland. The local farms have recognised that they can get greater money for them by exporting them than producing other varieties or selling avocados in the local market. So some have turned to focus solely on the production of Hass avocados. Unfortunately they require larger quantities of chemicals in their monoculture production and these chemical s are becoming a major issue in Pijao: the locals say that chemicals are destroying the land and leeching into the water systems and they are afraid of the negative impacts on health associated with these chemicals. The locals are looking for alternatives: ways of encouraging smaller scale production for local markets.

Another challenging issue in Pijao is in the area of planning for tourism. Engaging with the Cittaslow requirements has put Pijao ‘on the map’ and they are receiving more tourists each year. At the moment it is mostly in tours and day trips, but they recognise that they have a very small number of hotels or hostels and that this is a potential area for growth. I sensed unease in the community in how this was being dealt with. It seems that the local Alcaldía is supportive to a certain extent of Cittaslow but in a recent large tourism proposal to the over all municipality the members of Cittaslow were not involved. I talked with quite a few people about how they felt about tourism and the resounding response was that they were afraid of their town being overrun with tourists and people from other parts of the country setting up all sorts of tourist attractions. The absolute detrimental effects of this are evident in one of Quindío’s major tourist towns: Salento. This was once as a peaceful hillside town but now it is absolutely appalling overrun with tourist shops, hotels catering for foreigners and, to me felt like a type of disneyworld. It had nothing to do with Colombia and everything to do with pandering to tourists whims.

When a place becomes popular a number of things happen: the number of tourists increase and they begin to demand different services, people come in to create those services in order to get tourists to stay, local prices for every things rises because tourists do not know what the prices should be and are willing to pay the higher prices, locals get pushed aside and soon you have a morphed idea of what the place once was. Many of the people of Pijao are aware of this destructive quality and together they hope to take their time and create a more reasonable approach but there are others who want t push ahead with the standard way of doing things and welcome in any business that is willing to set up there.

“We don’t want business people that build big resorts and that our inhabitants become employees of foreigners. We are proposing family hotels … and hiking for small groups led by local people” Mónica Flórez.

I spent a few days chatting to locals and interestingly it was on my last day in Pijao that I got a chance to sit down and chat with Monica. We met in her lovely old family home and we talked for several hours about the town and how Cittaslow has been developing there, what motivates her and how she can continue to inspire change. She is a visionary, wonderfully creative and intelligent and able to see a more beautiful world, with a strong soul and so much passion. She needs it because as a single woman championing this project she comes up against lots of criticism. I had heard some of this criticism before meeting her. I found myself not judging her before hand but just listening to different perspectives and remaining curious about the project and to see what she was like. If I have learned anything on this journey it is that to understand a community you need to learn to look at it from as many perspectives as possible: the more the better! I loved chatting with her and I felt that we could have talked all day and I would have I only that I needed to get a bus that afternoon to meet friends in Medellin!

I found Pijao to be an absolute pleasure to be in with its slow and gentle authentic pace, the lack of tourists and the friendliness of all the people. The Cittaslow foundation is really a community support system for new ideas and a source of inspiration. It has allowed people to really look at their town and take pride in it: it ignited a fire that they felt had been quenched. It is inspiring and very exciting to see a community come together to create change. Slowing down has created new connections within the Pijao community: connections back to the earth: more awareness of the immediate environment, awareness of their collective social capital: the value of creating together:

“The great benefit of slowing down is reclaiming the time and tranquillity to make meaningful connections–with people, with culture, with work, with nature, with our own bodies and minds. Some call that living better. Others would describe it as spiritual.” In Praise of Slowness – Carl Honoré

What Pijao and the Slow movement gave me is hope and faith in the small and steady things that we can do in our day-to-day lives. What I saw in each project in Pijao was that people found a thing that you love in life, something that fills them with passion, they dedicated themselves to it and to sharing it within the community. If you are doing what you love your simple slow actions can have wonderful inspiring and maybe even big effects in the world, but do what you love, honour your creativity and the one that you are.

We live on a planet that is very much alive, and we are inextricably a part of this aliveness: we breathe within the same air systems, we eat the food from the same food systems, we drink the water and we are warmed by the sun. We cannot live separately to it even if our economic system ‘theoretically’ says we can, we are simply part of these systems of interdependency. Our monetary system as is stands is not taking into account our welfare, our happiness, our health or the health of the systems within while we live. We need to realise that the economy needs to serve us within a healthy living system and not the other way around.

Through our actions and daily transactions we can make changes to support our local economy, local arts and crafts, local music etc. Each of these choices helps strengthen our community fabric and strengthens our social capital. At the end of the day our economic system can come and go but what increases our quality of life is our connections to one another and to the places we live.

Thank you to everyone I got to speak to in Pijao, for your openness, your enthusiasm and your commitment to creating better ways of living.

My project of exploring community is fully supported through my creativity: through the sale of my art and by a virtual online community through crowd funding. If you would like to support me on this journey you can check out my art on www.sineadcullen.com or make a donation on my Crowd funding campaign https://www.gofundme.com/LetsCreate or through PayPal by using my email address: sinead.a.cullen@gmail.com

REFERENCES

My disclaimer: I am not an economist. This piece covers a HUGE topic of discussion and I have touched on just some aspects of a system that is astoundingly complex… excessively so, I believe. I am no expert but there are experts out there and many amazing people researching, writing and sharing new ideas on this topic. If you like or don’t like what I have written, if it scares the crap out of you (as it does me) or if you are inspired or if you are just curious to learn more please refer to the links below and/or go and research this for yourself and please share with me what you learn.

MONEY

- The Gold Standard Link 1 Link 2

- FIAT money

- FIAT money explained

- Fractional reserve Banking

- How is money created

- Money creation and Fractional Reserve Banking in the US

ECONOMICS

- Sacred Economics – the Movie

- The Economy for the Common Good

- What if the common good was the goal of the economy? Christian Felber

- GDP and GPI

- GPI

- Debt – Energy and the Economy Link 1 Link 2

- Chronology of money timeline

- European Monetary System

MEASURING HAPPINESS

THE SLOW MOVEMENT

- The Slow Movement http://www.slowmovement.com/

- Citta Slow

- Slow food

- Pijao and Cittaslow

- Pijao

- Finca La Granada – https://beanlinked.com/news/a-sustainable-approach-to-coffee-farming/

BOOKS

- Chambers, Simmons and Wackernagel (2000) Sharing Natures Interest – Ecological Footprints as an indicator of sustainability. Earthscan

- Eisenstein, Charles (2011) Sacred Economics Money, Gift, and Society in the Age of Transition Evolver Editions

- Hawken Lovins & Lovins (1999) Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution. Little Brown and Company

Recent Comments